“The work of art is limited to an ‘acting out,’ not an understanding. If it were understood, the need to do the work would not exist anymore… Art is a ‘guaranty’ of sanity but not liberation. It comes back again and again.”

Louise Bourgeois 1992

Art has long been a powerful medium for expressing the inexpressible, offering a visual language for personal experiences, unconscious fears, and unresolved emotions. It allows the artist—and, in turn, the viewer—to confront inner conflicts, traumas, and unresolved narratives that evade words. Lindsay Pickett’s paintings exemplify this process, blurring the line between the beautiful and the grotesque, the human and the monstrous. His surreal hybrid creatures, part-animal and part-human, serve as visual metaphors and containers for personal loss, emotional alienation, and existential dread.

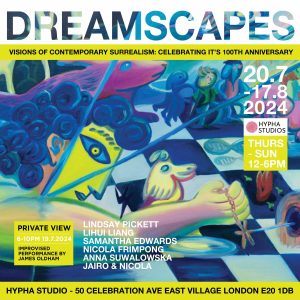

When I first encountered his work at the Dreamscapes exhibition by Hypha Studios in East Village Stratford, I was immediately drawn into these strange, unsettling worlds populated by uncanny beings—some with reptilian jaws and sinewy limbs, others bearing fragmented traces of human forms. Bright, dreamlike colours contrast darker elements, mirroring the tension between vitality and decay. In conversation, Lindsay shared how these hybrids emerged from artistic experimentation and the emotional challenges of his life—his struggle to navigate personal loss, a friendship that ended abruptly, and the journey of coming to terms with his neurodiversity.

When I first encountered his work at the Dreamscapes exhibition by Hypha Studios in East Village Stratford, I was immediately drawn into these strange, unsettling worlds populated by uncanny beings—some with reptilian jaws and sinewy limbs, others bearing fragmented traces of human forms. Bright, dreamlike colours contrast darker elements, mirroring the tension between vitality and decay. In conversation, Lindsay shared how these hybrids emerged from artistic experimentation and the emotional challenges of his life—his struggle to navigate personal loss, a friendship that ended abruptly, and the journey of coming to terms with his neurodiversity.

Lindsay’s artistic evolution, from early cityscapes to surreal creatures, reflects his search for coherence amidst life’s unpredictableness. As he reveals in this interview, his work is a way of grappling with unresolved relationships, including the sense of abandonment and rejection he felt throughout his life. In his current series, these hybrid beings are both the product of imagination and a means of exploring deeper questions about identity, genetic manipulation, and the irreversible nature of trauma. Through these visual narratives, Lindsay invites us to reflect not only on the fragility of human connection but also on the ways in which we carry the scars of loss and transformation.

A: You’ve been painting and exhibiting your work for some time now. How has your career evolved over the years?

L: Yeah, I’ve been painting and having the odd show here and there. Things really changed for me in 2017 when I went back to adult education. I started working as a part-time tutor around then, too. But selling my work has always been difficult. I sell pieces "here and there," but it’s not easy.

Painting started with cityscapes and playing with perspective, but then I began experimenting with hybrids—strange monsters and beasts. That idea has always been with me. However, I struggled with switching between different styles and themes. One of my tutors told me I needed to “settle on an area," so I did. That’s when I began focussing on hybrid animals in a nonsensical, surreal manner.

A: You mentioned hybrids. Why are you drawn to painting them?

L: I’ve always been fascinated by hybrids. It probably comes from a blend of my influences—artists like Bosch, Bruegel, and the surrealists like Dalí, Tanguy, and Magritte. During my BA, I was often told my work reminded people of them, especially Bosch. I’d be looking at an etching plate and suddenly see shapes, creatures, or something unusual. That’s when I started getting comparisons to Dalí. At the time, I didn’t understand my work that well. I painted what came to me without much reasoning behind it.

A: How has your process evolved since then?

L: Now, it’s more about ideas and reasoning. I’ve come to understand why I paint what I paint. Immersing myself in exhibitions, connecting with other artists, and being part of different communities have really shaped my practice.

A: Who or what inspires you?

L: Surrealism, Romanticism, Sci-fi horror, and genetic engineering. I link these influences to broader issues like how toxic our planet is. During my MA, I started painting hybrid animals with a different perspective. It touches on themes of surrealism and genetic engineering—ideas that are relevant today. My work is also influenced by Alexis Rockman and his focus on the environment and pollution.

A: How does your work connect to artists like Bosch, often considered the precursor to surrealism?

L: Bosch’s work is about a consequence and the morals of religion, the choices we make, and the repercussions. In Bosch’s time, people really believed that if you committed wrongdoing, you would be tortured in Hell by monstrous hybrids of man and beast. I see my work in a similar way. My hybrid creatures are metaphors for the idea that we’re all hybrids in some sense—genetically, socially, and even emotionally. We’re all hybrids of our parents, after all. However, these hybrids are the consequences of genetic hybridisation gone wrong and the prices we pay for playing God with ‘Mother Nature’.

A: That’s a fascinating concept. Do you feel your personal experiences influence your work as well?

L: Definitely. I’ve felt like a misfit for much of my life, especially in school and even within my own family. I felt ignored and sidelined, and I lost many friends along the way. It took me a long time to understand that I’m neurodiverse, and now I’m proud of it. Society is still evolving in its understanding of neurodiversity, and that lack of awareness made me dislike working in school environments.

A: You’ve mentioned a series of paintings focused on hybrid animals. Can you tell me more about that?

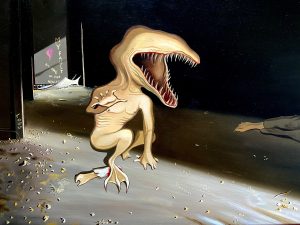

L: Yes, I’m currently working on a series where these hybrid animals exist in their natural habitats but are seen as different and monstrous. One series, “Keep Out,” (see below), shows a hybrid creature that has become unrecognisable as human. In the paintings, a bitten-off hand appears, symbolising a part of myself that feels dead after losing a close friend. That loss inspired much of this work.

Title: Keep Out, Medium: Oil on linen, Size: 85cmx70cm

A: It sounds like you’re exploring some heavy emotional themes in your current work.

L: Yeah, my work is going through a “dark period.” Losing a friendship after a misunderstanding has deeply affected me, and I’ve been processing that loss for about two years now. It feels as painful as when I lost my father. However, I don’t connect the two events directly. My current paintings explore themes of loss, trauma, and abandonment. There’s a sense of dread in the work sometimes.

A: Is there a fear that you’ll run out of ideas?

L: Absolutely, that fear is there. But ideas keep coming. For example, I’ve been inspired by real-life creatures, like flesh-eating fish found in Brazil. There’s a lot of ugliness in my paintings, but that’s part of what I’m processing.

A: Amid all the darkness, do you think there’s room for beauty in your work?

L: Yes, for sure. Someone once said that some of the creatures in my work look like me. I’m not sure how they would know that, as they’ve never seen me naked [laughs], but maybe they’re right. Some of my new paintings feature creatures with ladylike shapes—legs, hips—but with the face of a hippo. There’s a strange beauty in dangerous creatures, like praying mantises or deep-sea creatures.

A: How do you approach creating these creatures?

L: Sometimes, I start drawing without knowing where it will go, but I tend to find images online to help develop my ideas. Some of the creatures in my paintings break free after killing the scientist who created them, seeking revenge for what was done to them. But the underlying theme is that it’s already too late—the experiment has been done, and the damage can’t be undone. Much like my relationship with that friend. Some things remain unresolved, and you can’t go back to change them.

Lindsay Pickett’s art lingers in the space between the familiar and the strange, balancing surreal forms with emotional depth. His hybrid creatures are unsettling, yet there is something undeniably human about them. In their awkward shapes and strange anatomies, they seem to echo the emotional contradictions we carry—our longing for connection alongside the fear of rejection, the inevitability of change, and the scars left by loss. These creatures, in many ways, become metaphors for the hybrid nature of identity itself—how we are shaped not just by genetics but by relationships, experiences, and the fragments of those we encounter along the way.

Through his paintings, Lindsay offers a space to reflect on what it means to live with unresolved emotions. His work does not aim to resolve or fix these contradictions but rather invites us to sit with them. Like the creatures that populate his canvases, some experiences—especially those involving loss—remain unchangeable, as reminders of what has been and cannot be undone. Yet within this darkness, Lindsay finds moments of beauty—whether in the elegance of a praying mantis or the strange allure of deep-sea creatures.

Through his paintings, Lindsay offers a space to reflect on what it means to live with unresolved emotions. His work does not aim to resolve or fix these contradictions but rather invites us to sit with them. Like the creatures that populate his canvases, some experiences—especially those involving loss—remain unchangeable, as reminders of what has been and cannot be undone. Yet within this darkness, Lindsay finds moments of beauty—whether in the elegance of a praying mantis or the strange allure of deep-sea creatures.

Ultimately, his art encourages us to confront the ambiguity of life. Some things, like broken friendships, can’t be repaired, and certain aspects of ourselves may never fully find resolution. But perhaps, as Lindsay’s paintings suggest, there is still meaning to be found in these fragments—in embracing the hybrid nature of our own emotional landscapes, where beauty and monstrosity coexist.

To see more of Lindsay’s work, go to:

https://www.instagram.com/lindsaypickettart/?hl=en