More than just physical containers, our bodies serve as both the basis for who we are and the main lens through which we view the outside world. Our bodies affect how we perceive and engage with everything around us, from delicate touch sensations to intense emotional power. Psychoanalysis offers an additional layer of understanding by demonstrating how our unconscious mind can physically leave marks on our bodies that have a significant impact on our thoughts and behaviours. This essay will explore, implicitly and ambiguously, the complex relationship that exists between the body, perception, and psychoanalysis.

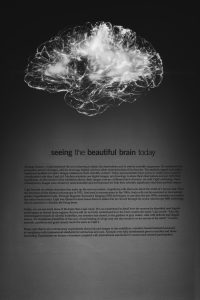

The brain is mysterious. We know only a portion of what there is to know about the brain, or the cosmos, for that matter. Perhaps, for that reason, we keep producing original and amusing ideas about both.

The brain is mysterious. We know only a portion of what there is to know about the brain, or the cosmos, for that matter. Perhaps, for that reason, we keep producing original and amusing ideas about both.

The brain itself is a soft, jelly-like mass of billions of cells and their connections. It weighs 2.15 to 3.15 pounds. The human brain regulates, through electrochemical energy, conscious and unconscious sensation, perception, and behaviour, as well as sympathetic and autonomic activities of the internal organs. In the brain stem and the limbic system, we experience our commonality with animal ancestors and relatives. As the base of the crown chakra, the brain contains our fantasies of a ‘higher’ universal mind.

The ancients thought of the locus of consciousness as the abode of thought and feeling located in the heart, chest, or liver. Only recently has the brain been thought to be the locus of consciousness. Nevertheless, the brain was imagined to be potent. The Irish mixed the brains of the fallen warrior with earth, fashioning a ball to be used as a projectile weapon. Many of our ancestors ate the brains of their enemies to assimilate powerful mana and assume dominance. For others, the brain was holy; in Crete, horns were thought to grow out of the brain as a sign of procreative life force. Our fascination with the brain speaks to its symbolic function as an imaginal container for a timeless and unbounded process that resolves opposites and divisions.

When one considers the brain from the perspective of the psyche, one is left with mental maps and images of geography, as well as emotional and memory centres, distinct intelligence areas, specialisations, localisations, and divisions between the left and right hemispheres of the brain. More recently, postmodern images of networks and fields, neural ecosystems, plasticity, and mirroring have also been observed. The advantages of specialisation and holistic functioning bring together the long-standing opposites found in psychological experience: undesirable fragmentation and idealised wholeness, within our conceptual framework of the brain. Scientific and technological developments have an equal impact on our understanding of the brain, as do our imaginations about the basic nourishment we receive from brainstorming and brainwashing. As we look deeply into images of both the brain and space, we also see the psyche imagining itself.

Skin is a responsive tactile boundary between self and other and the inside and outside of the individual. Skin is vital to survival, it is the place where two can meet. We often refer to the quality of skin’s symbolic containment or permeability: one is thinskinned or thickskinned. The irritating facts of life go “under one's skin”; one does the essential or compromising thing to “save one’s skin”.

Skin is a responsive tactile boundary between self and other and the inside and outside of the individual. Skin is vital to survival, it is the place where two can meet. We often refer to the quality of skin’s symbolic containment or permeability: one is thinskinned or thickskinned. The irritating facts of life go “under one's skin”; one does the essential or compromising thing to “save one’s skin”.

The skin is the largest organ of the body, it has a protective and cushioning function and is waterproof, elastic, breathable, and washable. The skin develops from the same foetal tissue as the brain and works actively with the hormonal, vascular, immune, and nervous systems. The skin enables us to perceive via pressure, temperature, and pain. Touch is a remarkable source of sensation, it is one of the first senses to activate in neonates and one of the last to subside in the elderly. Infants of many species appear to thrive on tactile contact, including human children. Such touch can foster greater connectedness and self-containment. Because skin is so nuanced in its reaction to the environment, it acts as a barometer for physical and psychological well-being. While health and relative balance often register in the bloom of the skin, illness, undesirable contact, or psychic conflict may manifest in blushing, rashes, inflammation, or allergy.

The skin serves as a canvas for the symbolic representation of one's social standing and individual identity. Skin colour, determined by the amount of melanin or brown pigment produced by the individual, has been the primary source of ethnic and racial distinction. Our perceptions of ourselves and others have been profoundly impacted by psychological projections surrounding skin tone. What "only" penetrates the skin is multi-layered and not at all superficial.

The eye receives and emits light, looks in and out, and is a window to the soul and the world. It can see too much or nothing at all. The eye illuminates, stares, understands, expresses, and protects. We can truly feel known by the way another’s eyes take us in, we can feel despair and sorrow at being "unseen.”

The eye receives and emits light, looks in and out, and is a window to the soul and the world. It can see too much or nothing at all. The eye illuminates, stares, understands, expresses, and protects. We can truly feel known by the way another’s eyes take us in, we can feel despair and sorrow at being "unseen.”

Losing one's sight or an eye can inspire truly creative work. The possibility of changing from one form of consciousness—seeing—into another is symbolised by missing or lost eyes. It can be used to describe awareness and sight that respond more to an inner vision than to sensory inputs. While light, insight, intelligence, reason, and spiritual awareness are traditionally associated with the eye, the inner eye sees with a night vision and dark awareness into the wisdom of dreams and all the unconscious and emotional elements that also make up full human understanding.

The play of opposites, which includes the two eyes of inner/outer, blind/sighted, solar/lunar, illuminating/deadening, and open/closed, opens up one-dimensional vision and ultimately resolves into a more advanced form of unified vision.

Sounds, the movement of waves and wind noise in nature, and the sounds of a city travel inward through the complex labyrinth of the human ear. It is a direct reversal of Plato’s theory of sight as a projection of fire outward. The ear collects these waves in its cartilaginous pinna, directs them along spiral coils formed by the shape of the vibrating sound, and stimulates the eardrum to send the waves through three of the hardest and tiniest bones in the body - the hammer, anvil, and stirrup. These bones amplify air pressure in the Eustachian tube, which exerts pressure on the fluid in the innermost chamber, the snail-shaped cochlea. Sound perception is then transmitted to the auditory cortex via acoustic nerves in tiny hairs suspended in the fluid. Each hair corresponds to a different frequency. Because the inner chamber is only filled with fluid as animals evolved from aquatic to land animals, we can better understand the ear’s other vital function, which was to maintain our sense of balance after we lost the support of seawater.

Sounds, the movement of waves and wind noise in nature, and the sounds of a city travel inward through the complex labyrinth of the human ear. It is a direct reversal of Plato’s theory of sight as a projection of fire outward. The ear collects these waves in its cartilaginous pinna, directs them along spiral coils formed by the shape of the vibrating sound, and stimulates the eardrum to send the waves through three of the hardest and tiniest bones in the body - the hammer, anvil, and stirrup. These bones amplify air pressure in the Eustachian tube, which exerts pressure on the fluid in the innermost chamber, the snail-shaped cochlea. Sound perception is then transmitted to the auditory cortex via acoustic nerves in tiny hairs suspended in the fluid. Each hair corresponds to a different frequency. Because the inner chamber is only filled with fluid as animals evolved from aquatic to land animals, we can better understand the ear’s other vital function, which was to maintain our sense of balance after we lost the support of seawater.

The psychoanalyst Theodor Reik, who once claimed that the invisible and intangible can still be audible, suggested that we can truly hear through greater use of our intuition.