From grand castles to cosy cottages, the image of a house has captivated humanity for centuries. But a house is more than just a physical structure; it's a potent symbol that transcends cultures and time. This blog will delve into the rich symbolism of the house and home, exploring how it reflects our deepest desires for security, belonging, and self-discovery.

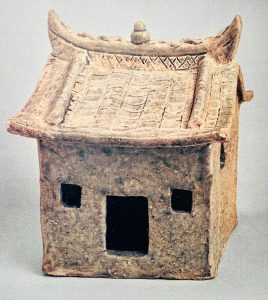

One of the oldest representations of a house is a little ceramic Chinese house from around 2000 years ago (ca.25-220 C.E). Its rudimentary windows and door convey the essence of a house as containment and shelter. A house is one embodiment of home; “home is where the heart is”. A feeling state of belonging, contentment and safety. Physically, our earliest home is the maternal womb in which we are gestated. Animals instinctively make their homes in nests, burrows in the earth, the hollows of trees, caves and clefts; many first homes of humans were intimate, encompassing, womb-like structures. All over the world cave drawings attest to our primordial presence.

One of the oldest representations of a house is a little ceramic Chinese house from around 2000 years ago (ca.25-220 C.E). Its rudimentary windows and door convey the essence of a house as containment and shelter. A house is one embodiment of home; “home is where the heart is”. A feeling state of belonging, contentment and safety. Physically, our earliest home is the maternal womb in which we are gestated. Animals instinctively make their homes in nests, burrows in the earth, the hollows of trees, caves and clefts; many first homes of humans were intimate, encompassing, womb-like structures. All over the world cave drawings attest to our primordial presence.

Mud huts in Africa are still fashioned in the form of a female-like torso. The teepee of the Great Plains Indians, the triangular tents of the nomads, are circular at the base, suggesting the alpha and omega existence that begins in the womb and the eternal cycles of nature. To be unhoused does not necessarily mean to be homeless. Home could be projected onto a particular city, a beloved friend, a ship at sea, or a set of circumstances. These correspond to the experience of both fixity and freedom. In dreams, the psyche is often depicted as a house. Sometimes there are different levels representing a continuum of time. There may be familiar rooms, other unknown, hidden, revealing multivalenced potentialities.

Home has to be idealised. In mythology, our first home is a paradise of oneness, a time before consciousness and its conflicting discriminations. Home can be also a prison or a haven of avoidance. Home can represent the nurturing of the self or its violation. We escape home, seek home, outgrow home, return home. Home is the goal of epic odysseys, spiritual quests and psychic transformations.

An essential part of a home is a window. It is a transparent threshold. It is an opening in a wall that lets in air, moonlight, sunlight, the colours of the world, and the dark of the night. The window is where inside and outside meet bringing together two worlds and their elements. Eyes have been called the windows of the soul. The word window is derived from the old Icelandic “vindr” wind and “auga” eye. The wind-eye was originally a hole in the wall protected by branches or a curtain exposed to the wind. Over the centuries the hole in the wall was screen by a rice paper, marble or thin panes of mica as a substitute for a glass. Eventually, being able to open and close, windows contributed to regulating heat and light and acquired the meaning of an interval of time in which something can occur.

An essential part of a home is a window. It is a transparent threshold. It is an opening in a wall that lets in air, moonlight, sunlight, the colours of the world, and the dark of the night. The window is where inside and outside meet bringing together two worlds and their elements. Eyes have been called the windows of the soul. The word window is derived from the old Icelandic “vindr” wind and “auga” eye. The wind-eye was originally a hole in the wall protected by branches or a curtain exposed to the wind. Over the centuries the hole in the wall was screen by a rice paper, marble or thin panes of mica as a substitute for a glass. Eventually, being able to open and close, windows contributed to regulating heat and light and acquired the meaning of an interval of time in which something can occur.

Doors can stand between here and there, between known and unknown. At the psychological level, gates are found between the inner and outer worlds, between sleeping and waking. So gates are the point of transition from one world to another. A mother’s body is the gateway opening to this world, the tomb, the gateway to what comes after death. In ancient Egipt, a doorway in the tomb was built to allow free passage- in and out to the soul. In our everyday life gates and doors are there to protect the house and the life of the family. The gate-doorway can be a numinous and dangerous place, rich in rituals and superstitions. Offerings and prayers are made, and shoes are removed before entering. One must step carefully over a threshold, usually right foot first, and should not sneeze, linger, or sit. On the other hand, sometimes doors and gates must be opened to release what is too confined inside. For example in folklore of the British Isles, house doors must be opened when someone dies to ease the passage of the soul.

Doors can stand between here and there, between known and unknown. At the psychological level, gates are found between the inner and outer worlds, between sleeping and waking. So gates are the point of transition from one world to another. A mother’s body is the gateway opening to this world, the tomb, the gateway to what comes after death. In ancient Egipt, a doorway in the tomb was built to allow free passage- in and out to the soul. In our everyday life gates and doors are there to protect the house and the life of the family. The gate-doorway can be a numinous and dangerous place, rich in rituals and superstitions. Offerings and prayers are made, and shoes are removed before entering. One must step carefully over a threshold, usually right foot first, and should not sneeze, linger, or sit. On the other hand, sometimes doors and gates must be opened to release what is too confined inside. For example in folklore of the British Isles, house doors must be opened when someone dies to ease the passage of the soul.

A stairway leads one up or down. The etymology of the word drawing on Old English words “stigan”- to climb and “staeger”- riser, suggests that stairs are primarily perceived as going up rather than both directions. This furnishes a symbol for ascents in slow stages and transitions through difficult steps. We see this externally in the stepped pyramids of ancient Egipt whose stairways provided a transitional zone between life and death. But staircases not only ascend, they also go down. In myths and fairytales or dreams the staircases descend into realms of mystery, magic, treasure, and imagination. Psychoanalysis taught us to search for our own descents for meaning. Freud used the French phrase ‘esprit d’escalier’ (wit of the staircase) to refer to repartee(*1)that occurs to us as we depart after an argument. The gain of creative wit by reclaiming our lower nature through psychoanalysis led Freud to reject what he considers the pretences of sublimation(*2).

A stairway leads one up or down. The etymology of the word drawing on Old English words “stigan”- to climb and “staeger”- riser, suggests that stairs are primarily perceived as going up rather than both directions. This furnishes a symbol for ascents in slow stages and transitions through difficult steps. We see this externally in the stepped pyramids of ancient Egipt whose stairways provided a transitional zone between life and death. But staircases not only ascend, they also go down. In myths and fairytales or dreams the staircases descend into realms of mystery, magic, treasure, and imagination. Psychoanalysis taught us to search for our own descents for meaning. Freud used the French phrase ‘esprit d’escalier’ (wit of the staircase) to refer to repartee(*1)that occurs to us as we depart after an argument. The gain of creative wit by reclaiming our lower nature through psychoanalysis led Freud to reject what he considers the pretences of sublimation(*2).

Notes:

(*1) Sigmund Freud didn't originate the term "esprit d'escalier," but he did discuss this phenomenon. It's a French expression that literally translates to "staircase wit," referring to the feeling of thinking of the perfect comeback or response only after the conversation or situation is over. Freud believed this experience stemmed from the unconscious mind, with witty retorts being blocked in the moment due to social inhibitions or anxieties.

(*2) In psychoanalysis, sublimation is a mature defence mechanism where unacceptable urges or desires are channelled into socially acceptable and often productive outlets. It's a way of transforming negative or undesirable impulses into something positive and beneficial.

For example, an aggressive urge might be channelled into competitive sports or debate. Or, someone experiencing heartbreak might pour their emotions into creative writing or music.